Britain’s economy is the closest it has been to full employment since the early 1970s — with the jobless rate now at 4 per cent — and companies are finding it harder to hire the right workers. Some companies are expecting it will become even more difficult to recruit once the UK leaves the EU because the government is proposing a new immigration regime that lets some high skilled workers into the UK but places curbs on untrained labour.

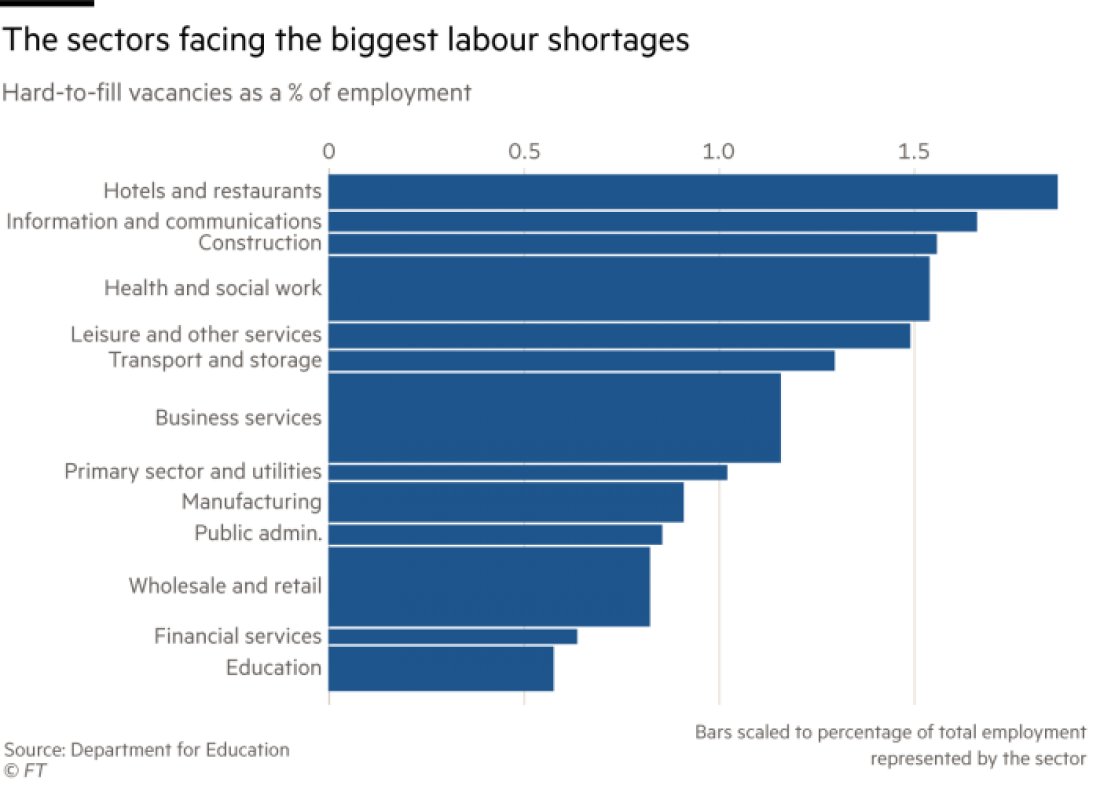

After years of sluggish wage growth, low unemployment is now starting to hit companies’ profits: JD Wetherspoon, Royal Mail and Ryanair have recently complained about rising labour costs. The Financial Times has reviewed official and other data to identify several sectors of the economy that are grappling with acute labour shortages, and below are the findings.

Hospitality

Chefs were the most in-demand skilled trade in the UK last year, according to the 2017 Employers Skills Survey compiled by the government and published in August. This was one reason why hotels and restaurants had the highest level of so-called hard-to-fill job vacancies of any part of the British economy in the survey. These figures have been backed up by the latest official labour market statistics, from August, which found that accommodation and food services had the highest vacancy rate of any industry in the UK — with 4.1 advertised positions for every 100 people employed in the sector. JD Wetherspoon, the pub chain, on Wednesday issued a profit warning as the company also said it was raising wages for staff amid record low unemployment.

Demographics are the problem, said Kate Nicholls, chief executive of Hospitality UK, a trade body. About half the workers in a sector that encompasses everything from coffee bars to nightclubs is aged under 30 and there are far fewer 18 to 24-year-olds entering the jobs market because of a dip in the birth rate around the millennium.

“It’s what makes Brexit . . . so worrying for hospitality,” added Ms Nichols. “It’s not skill shortages, not a failure to upskill our workers, simply a shortage of bodies available.” There is, however, a shortage of qualified chefs because the number of people going to catering colleges has declined.

Information technology

Information technology was last year the sector with the second highest proportion of hard-to-fill vacancies, the Employers Skills Survey found. IT is the most in-demand skills set this year across multiple industries, according to a survey published last month by the Recruitment and Employment Confederation, an industry trade body.

Software engineers and programmers were particularly sought after, with many respondents to the survey mentioning automation, the C++ and C# programming languages and cyber security as key skills. “It’s a high growth area, the tech sector specifically, and we’re not producing the right skills domestically,” said Vinous Ali, head of policy at Tech UK, a trade body.

IT workers from overseas were frequently finding they were unable to move to the UK last year, she added, as the sector bumped up against a cap on so-called Tier 2 visas issued by the UK government to skilled workers. “Businesses [will go] elsewhere if they can’t get access to the right people here in the UK,” said Ms Ali.

Construction

The building trade had the greatest rate of vacancies based on skills shortages, meaning positions left open for six months or more because of a lack of adequately trained applicants, the Employers Skills Survey found. The sector also had the third highest rate of hard-to-fill vacancies.

The shortages of skilled workers is reflected in official wage growth figures. In the three months to August, year-on-year growth in real wages in the construction industry hit 4.6 per cent, compared with 3.1 per cent in the economy as a whole. Skills shortages in the sector have been common since 2014, when construction activity started to recover after the downturn following the financial crisis, said Rebecca Larkin, chief economist at the Construction Products Association, a trade body.

Many construction workers quit the industry during that downtown, she added, while a lot who stayed are now heading for retirement and some EU nationals may have been discouraged from coming to the UK since the Brexit vote. So far the skills shortages have led to higher wages and a squeeze on construction companies’ profits margins rather than higher costs for customers, said Ms Larkin.

Healthcare

Vacancies in the healthcare sector have surged during the past few years, according to official data. The vacancy rate has risen from 2 open positions for every 100 employed workers in 2013, to 3.2 now. The sector has been hit hard by austerity inspired public spending cuts since 2010. Workers in the National Health Service were affected by a public sector pay freeze, leading to remuneration falling in real terms, while local authorities cut funding for care homes.

Emily Andrews, associate director at the Institute for Government, a think-tank, said the government’s move to ease the pay cap was unlikely to be enough to end the recruitment and retention problems in the NHS. “The number of people leaving the NHS who cite work-life balance as their reason has doubled since 2011,” she added. “These pretty small pay increases are not going to be enough to counter that.”

Source: Gavin Jackson, November 8, 2018, Financial Times